The Panama Canal was opened on August 15, 1914. 109 years later, it remains at the heart of global shipping and geopolitical tensions. From its tumultuous construction to its enlargement, we take a look back at the history of this major structure.

Construction of the canal began under the direction of the French engineer behind the Suez Canal: Ferdinand de Lesseps. At the head of the “Compagnie universelle du canal interocéanique de Panama” and then accompanied by Gustave Eiffel, he began this colossal project in 1880. Climate, topography, tropical diseases and corruption slowed work, ruining the company and its 85,000 subscribers. Work stopped in 1889, leaving the canal unfinished. A few years later, the “Panama Scandal” broke out in France.

Following the French failure, the Americans resumed work in 1904, after supporting the independence of Panama, which seceded from Colombia in 1903. Under a treaty, they were granted a 10-mile strip of land around the canal in perpetuity, and completed the work in 1913. In exchange, Panama received $10 million and $250,000 a year, a derisory sum compared with the canal’s yields. The canal was finally handed back to Panama in 1999, but the United States controlled it throughout the 20th century. Its inauguration on August 15, 1914 went unnoticed in a Europe plunged into the deadliest conflict in its history, with Germany’s declaration of war on France 12 days earlier, on August 3, 1914.

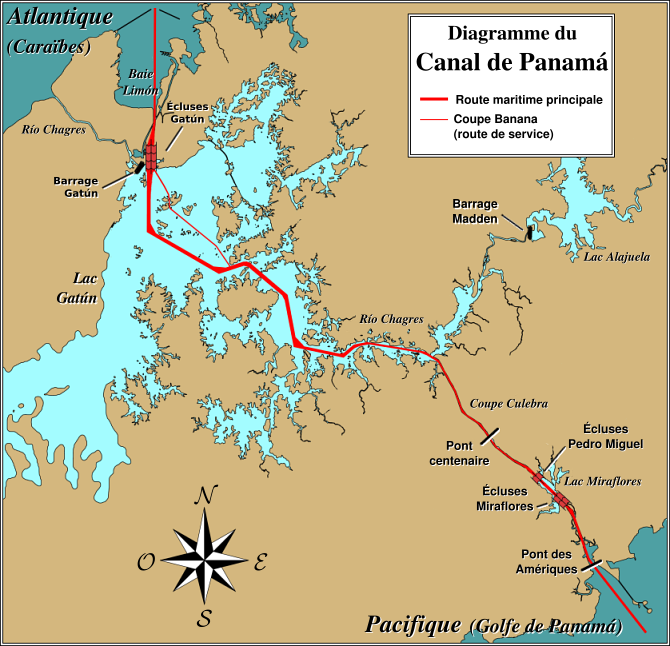

The canal had a lasting impact on global maritime traffic, starting with that of the United States, which could now sail from New York to San Francisco in 8,370 km, compared with 20,900 km previously, with the passage around Cape Horn to bypass South America. A revolution. It has also become the shortest route from the west coast of the American continent to Europe, and the fastest from East Asia to the east coast. An engineering feat spanning 77 km, it comprises 3 sets of locks and 2 artificial lakes.

Widening work, decided by referendum, started in 2006 and completed in 2016, was carried out in response to a number of major issues: the steady growth in international shipping traffic and the constant increase in ship size. Originally designed to accommodate ships up to 32 meters wide and 295 meters long (“Panamax” standards), the canal is now suitable for ships up to 49 meters wide and 366 meters long (“NeoPanamax” standards). The maximum capacity of ships that can navigate the canal has been increased from 5,000 to 13,000 containers.

The $5.2 billion project has adapted the canal to the ever-increasing density of maritime traffic, reducing crossing times to around 9 hours. Today, around 6% of the world’s maritime trade passes through the canal every year. In 2022, more than 14,000 ships passed through, or almost 38 a day, carrying 518 million tonnes of goods and earning the Panamanian state almost 2.5 billion dollars. The canal has become indispensable to Panama’s economy. It accounts for around 6% of its GDP, and more than 20% including indirect revenues. It has enabled this small Central American country to become one of the most prosperous on the continent, with a GDP/capita of $17,357 by 2022.

Despite this, the Panamanian authorities are worried about competing projects: the Nicaragua canal project, encouraged by China, and the prospects of exploiting the Arctic sea routes could also transform global shipping. These projects make them fear the prospect of competition and a substantial loss of revenue. Indeed, with the size of merchant ships constantly increasing, the canal is unable to accommodate the largest vessels, such as certain super container ships or super tankers.

But with the Nicaragua project at a standstill, and the Arctic routes not yet accessible year-round, the Panama Canal is likely to remain a major geostrategic point and an essential facility for maritime traffic and world trade for some decades to come.

Photo credits : Wikimedia Commons.

By Arthur Benoit