Few would suspect that 2,500 tons – the equivalent of 2,500 Renault Clio’s – and 75 men[3] are to be found below this water-splitting fin. Closing in can be heard the sound of the Gendarmerie’s motor launch and the swift craft bearing Marines, weapons at the ready, which will accompany it on its way out. The submarine, clumsy and vulnerable when surfaced, must be escorted to the nearby coast before diving, in order to warn off those ships which might present a danger to her.

Black-clad men, their coveralls waterproof and hot, rush about on her barely-surfaced fore and aft decks, under the supervision of the Petty Officer Cédric F., the master of the deck, the crew’s “mother”. Ship-handling appurtenances[4] are stored away. The towed linear antenna (TLA) is launched, with the assistance of a dedicated tug. The ship will tow this sonar, several hundred meters long, during her entire mission. It allows her to detect the low-frequency indiscretions of her targets at great distances. The ritual remains the same for every new mission. Once the manoeuvre has been completed, the SSN can accelerate and start on her journey to the high seas. The decks are inspected one last time to ensure no foreign body will hinder the water’s flow over the hull once the submarine is submerged.

On board, pre-diving measures are in full swing. All equipment is verified, hull openings and pipes are inspected, compartments are checked. SLt Brice K., the young deck officer, personally closes the last panel linking the submarine to the outer air after having secured the gangplank for diving, then descends to the navigation and operations command post (“poste de conduite de la navigation et des opérations”, or “PCNO”).

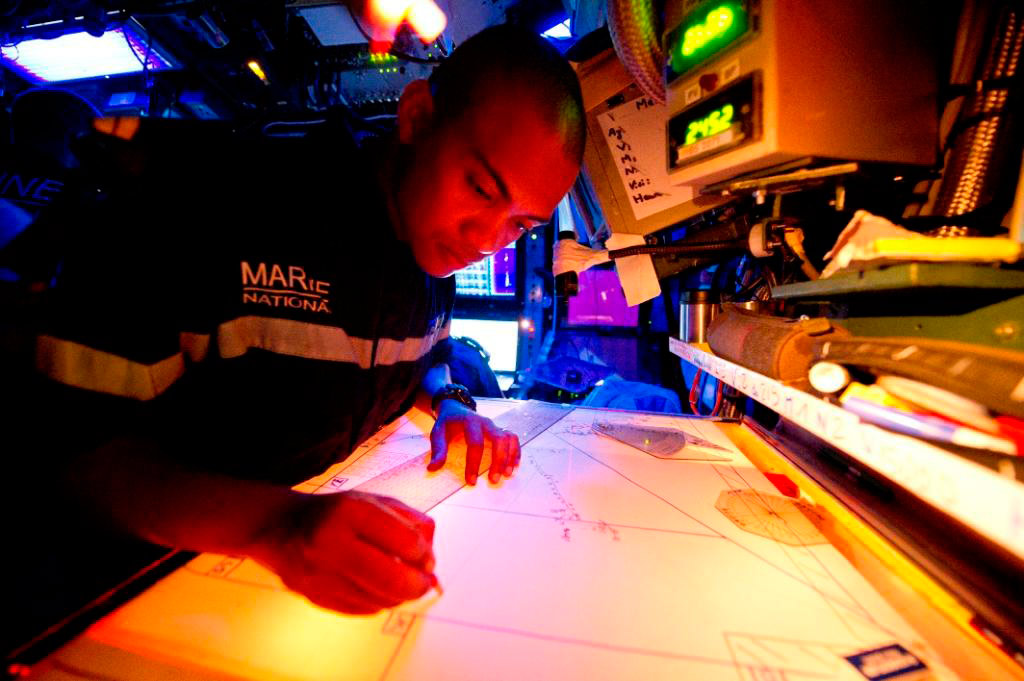

CPO David D., the officer of the watch (the “navigation” part of the PCNO), scrolls down his check-list. He is the orchestra leader of onboard life and ship security. After a few minutes, he calls out, “Submarine ready to dive!” The deck officer, with the commander’s permission, then gives the order to take the SSN down to periscope depth, i.e. just below the surface. The orders are transmitted throughout the ship for the entire crew to hear. The vents are open, allowing air to be removed and the ballast tanks to be filled with water.

The submarine enters the dark waters of the Mediterranean and disappears under its surface in less than two minutes. The ship is then trimmed by the head and stern under the practiced hands of the helmsman, to ensure that no air bubble remains in the ballast, as this could be a source of instability and noise. She is then brought back to periscope depth and periscopes are raised to check the tactical situation around the SSN during the leakage test. Reports are quick to come. The ship is watertight. His mind at rest, the commander can now record his orders for the night in the ship’s log. Instructions are transmitted to all watch stations. The submarine silently enters the depths and discreetly heads for her next patrol zone.

Meticulous, demanding preparations

Each member of the crew has gone over each action, each reaction to possible incidents and damages, under the eye of the instructors of the school of submarine navigation over the two months of on-shore training that precede a mission. Teams were then tested for three weeks in on-board simulations, under every conceivable configuration and scenario, before the “training” division of the SSN squadron, acting as external auditors, certified them as being “operational and unrestricted”. Such was the case of the “blue” crew of the Saphir after it had successfully completed this qualification period.

Before being allowed to sail, the ship also spent five weeks under the expert care of the DCNS shipyards for a complete overhaul. At the same time, the crew performed a significant part of the labour, getting her for her nest mission, loading her tactical weapons (F17 mod 2 wire-guided torpedoes, Exocet SM39 missiles) and some two months’ supplies onboard. So both the submarine and her crew were examined, verified, overhauled and prepared until they received an overall green light for D Day, or Departure Day. The SSN’s first dive, which went off without incident, is proof of this.

The men of the Saphir are also mentally prepared for their job and for the four months the coming mission will last. Naturally, families are the chief concern. The crew’s emotional stability demands that they be aware that all is well at home. Otherwise, it would be very difficult for them to remain cut off from their loved ones for months. So family context is specifically monitored before the start of a mission. The Cdr Benoît F., the executive officer, with the help of the bridge commander and section heads, is ever on the look-out for possible family concerns among his submariners, to help them as best as possible before the ship gets underway, even if it means leaving someone ashore if the problem cannot be solved.

Only volunteers may serve on submarines. While anyone can apply to become a submariner, not everybody chooses to continue in the silent service: this passionate profession is demanding and restrictive. So the personnel on board a ship is extremely motivated and rather young. The average age is 28. The youngest aboard is “the kid“, Seaman Kevin M., 19, future cook. He washes dishes and helps in the galley. He is a valuable “newbie” for any kind of general task that needs to be done. The oldest is the “old man”, the “pasha” or commander, depending on the tag, Cdr Olivier B., 39.

Twelve years to train an SSN commander

It takes about twelve years to train an SSN commander. He must go through two years of theoretical training, four positions of responsibility, over ten operational cycles, and some 15,000 hours of underwater service. To top it off, he must pass the famous command course, COURCO. Every step is mandatory. Any failure in any position, course, training or practice can become an ejection seat. And above all the COURCO, the Holy Grail and pet peeve of every submariner officer wishing to assume command one day. Without it, there’s no hope: one will inevitably be asked to leave the submarine service! Created by the British after World War I to reduce the excessive attrition rate of their submarines, it became known as the Perisher. And it bears its name well: between one quarter and one third of all trainees fail in each course, a rate which still holds today, in both the British and the French Navy. This, a veritable life-size test, conducted on simulators and later at sea, is designed to evaluate future commanders in every conceivable situation and to discover whether they will be able to make the right decisions, even – and especially – under great pressure. Such rigorous selection principles are necessary: a submarine consists of an extremely complex machine to command and a group of men whom it is no easier to lead in tense operational situations.

The same stringent selection process is applied to the entire crew, at all levels. But the submarine is an amazing life experience. As soon as they join the submarine forces, the men are taught to understand and employ this extraordinary tool, to coexist, to help each other. The challenge is daunting, no doubt, but there is someone to help them meet it. Comradeship is the state religion on board: old hands are constantly helping the newcomers to grow. No effort is spared, no means denied to help them succeed, so long as they show themselves to have the required discipline, stubbornness, and willingness to go the extra mile. A submariner’s job is an extraordinary one, carried out by “nearly” ordinary men.

An essential instrument of power

A few days after discreetly crossing the Strait of Sicily, the Saphir nears her zone of operations off the coasts of a Mediterranean country. The crew rotates by watch. Half of them are at their watch stations, to decrease reaction times and have the various stations manned by the best people. The other half tend to their duties: maintenance of material, debriefing of previous watches, preparation for coming ones, and rest.

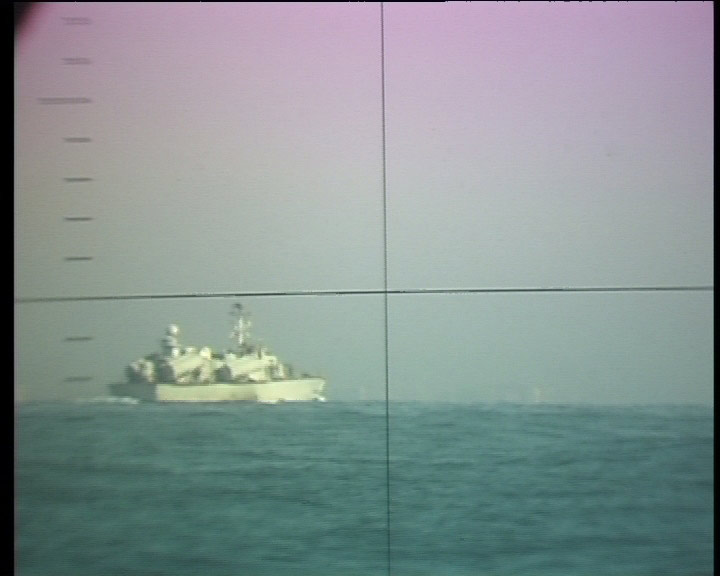

The SSN goes back to periscope depth near the coast. She is traveling just below the surface, at reduced speed to minimize her wake. At the periscope, the commander is determining the tactical situation while all sensors on board the submarine are on alert: radar transmissions, radio communications, sonar signals, everything is recorded and interpreted. A sonar trace is detected coastward, near the harbour’s outlet. CPO Benjamin L., watch analyst or “golden ear”, takes over the flank sonar monitoring and reroutes the analysis to his workstation. Hands on his earphones, he closes his eyes, cutting everything else off, then looks at his screen and calls out, “Speed estimate, over 30 knots, three props, most likely an Osa-class motor launch.”[5]The commander, trusting his sonar specialist’s classification, orders all masts to be lowered, dives to security depth, and starts chasing the motor launch at top speed. A half-hour later, after complex interception calculations, the SSN rises to periscope depth near the motor launch and confirms the announced ship class. He takes the opportunity to observe, safe from harm, the target ship’s behaviour while controlling his own ship’s noise, to avoid counter-detection. The acoustic and electromagnetic signatures of the Osa are updated, her communications intercepted. For the next few days on patrol, she will be easy to identify.

The SSN could just as easily have sunk this ship had the situation warranted it. Her gift for ubiquity, with the enemy never knowing exactly where she is to be found, her discretion and firepower, all combine to make her a dangerous huntress and to represent a constant threat in her zone of responsibility. This is a strategic vector and a naval-power asset which no country with international ambitions, such as France, could easily do without, which is one of the reasons for the Barracuda program and the planned unit-for-unit replacement of the Rubis-class SSN.

Six ships replaced, unit for unit

The first Barracuda, the Suffren, will enter active service in 2017. This class of SSN offers numerous innovations. The areas of discretion and acoustic detection, as well as the combat system, will benefit from the technological progress achieved on Le Terrible, the latest next-generation, nuclear-powered, ballistic-missile submarine (SSBN). Her above-surface detection, transmission and interoperability abilities will also be significantly increased. Finally, two major developments will be added to perfect the future crown jewel of the submarine forces: the ability to strike at inland targets using the naval cruise missile (“Missile de Croisière Naval”, or “MDCN”), and the ability of discreetly deploying or supporting special forces, through an integrated swimmers’ airlock and a dry-deck shelter (DDS) that can be installed on the aft deck.

These future SSN will constitute dangerous strategic platforms that will permit this class of launchers to fully perform the entire spectrum of its assigned missions. Finally, as this major program is essential for the continuation of nuclear dissuasion at sea, one may reasonably expect to see it carried through, despite coming periods of budgetary cuts… unless France should wish to reduce her international ambitions.

* Cdr Olivier Burin des Roziers, currently training with the 20th promotion of the Ecole de guerre (France’s Command and General Staff School), commanded the patrol boat Le Gracieux in French Guyana, as well as the blue crew of the nuclear attack submarine Saphir.

[1] “SNA”, for “Sous-marin nucléaire d’attaque”, in French.

[2] The 2008 White Paper defined five strategic functions: dissuasion; intelligence and anticipation; prevention; intervention; and Protection.

[3] Unlike those of other ships in the French Navy, submarine crews are currently not feminised.

[4] “Ship-handling appurtenances” refers to every piece of equipment used in carrying out these operations: windlasses, hoists, davits, ground tackles, hawsers…

[5] NATO code for one of the swift missile-launching patrol boats developed by the Soviet Navy in the early 60’s and sold to many navies around the world.

DCNS, the world leader in naval defence, works to renew the french submarine fleet

Between 2017 and 2027, Barracuda-type SSNs will replace the Navy’s current-generation Rubis/Améthyste-class boats. Mission capabilities will include intelligence gathering and special operations (by commandos and special forces), anti-surface and anti-submarine warfare, land strikes and participation in joint operations wherever the type’s interoperability and associated capabilities (discreet communications, tactical datalinks, etc.) are required. The weapons payload will include next- generation type F21 heavyweight torpedoes, SM39 anti-ship missiles and MdCN naval cruise missiles.

The Combat System under development for Barracuda-type SSNs combines an advanced sonar system based on that developed for the Navy’s current-generation nuclear-powered ballistic missiles submarines (SSBNs), an optronic mast replacing the traditional optical periscopes, a weapons system with twice the capacity of that carried by Rubis-class SSNs and a combat management system (CMS) integrating the capabilities of all of the boat’s above-water and underwater surveillance sensors.

The Barracuda programme represents a vital contribution to the renewal of France’s naval forces and a significant proportion of the group’s production workload as it will keep DCNS teams and facilities busy until 2027.

In December 2006, the DGA awarded the overall Barracuda contract to DCNS, appointing the group as programme prime contractor and Areva-TA as nuclear powerplant prime contractor. The firm order placed at the same time calls for the development and construction of SSN Suffren, the first of six Barracuda-type SSNs. The contract also covers through-life support for all six submarines during their first years of operational service. The second and third tranches, confirmed in 2009 and 2011 respectively, cover the construction of the second- and third-of-type SSNDuguay-Trouin and SSN Tourville.

Source DCNS